Why the media matters and why it doesn't

Have you heard? The News is on the news. We are being manipulated. Trust in the media is at an all time low. They don’t make good movies and music anymore. Blah blah blah.

There is a lot to be said about this, and many people have said far too much. It seems that the media is at once the most powerful yet irrelevant force that we should ignore and also obsess over. We cannot help but be amazed, entertained, disgusted, and (allegedly) controlled by the media. Conspiracy theories abound, newsmen deny them but tie the noose harder around their necks in the process.

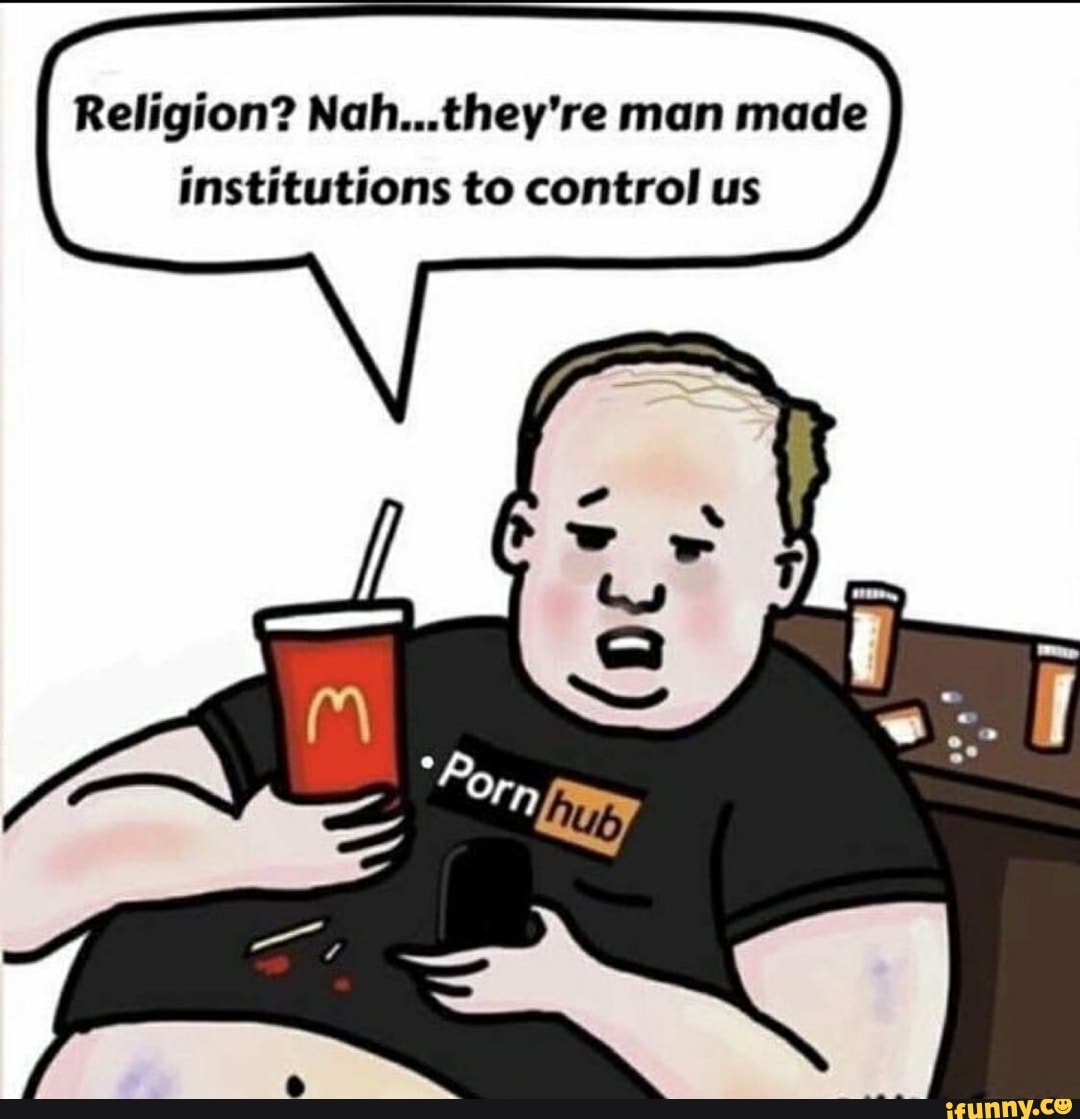

Mass media (pop culture and news media) is clearly very relevant because of its ability to subvert human empathy, replace traditional belief systems, and getting people to care about quasi-reality (things that are objectively real, but may as well be fictional). Some believe that it is a force for good, a tool to educate and correct problematic behaviors. Others are more skeptical, suspicious of its power and motives. One thing has become increasing difficult to deny: it is not a neutral spectator in the arena of human affairs.

Humanization is fine, unless the human is fictional

Empathy is generally perceived to be a positive, civilizing force, one that reminds us of our common humanity. But it has one major weakness: scalability, or the lack thereof. I’m not quite as skeptical of empathy as psychologist Paul Bloom, but he is right to call it “hopelessly limited.” Once we reach beyond the relatively tiny group of people that we can truly love and hate, that we can laugh or cry with, that are real to us, the goals of empathy become murkier and tend to lose touch with reality.

What happens when you watch a celebrity doing non-celebrity things (being “relatable”) on a screen? Consciously, you know that the two of you are nothing alike. Unconsciously, you relate to this person, projecting your hopes and emotions onto him/her. The impulse for empathy can be weaponized in this way and used as a tool of manipulation. To empathize with a fellow human being should not be a one-way street. It’s not a good idea to humanize someone unless you have the opportunity to treat (and mistreat) them as a human being, and vice versa.

Traditional roles of religion and culture are being transferred

For many, pop culture and news media have replaced traditional religion in several aspects of their lives. This modern belief system has its own internal logic, moral precepts, and ideals for a good life. Devout followers are promised fame and fortune, while unbelievers are threatened with a life of obscurity and poverty. What’s more, it offers something that conventional religions never do: the chance to become one of the gods.

The idea of seeking moral guidance from pop culture is puzzling. Why should anyone expect to learn morality from something made to entertain us? Some people, especially conservatives, have always held popular entertainment in suspicion, blaming them for corrupting youngsters. Yet, the truth is even stranger. Nowadays, it’s not uncommon to come across people who expect pop culture to teach them how to be a better person, serving as an extension or even a replacement for traditional moral instruction.

This transfer of roles is something new and has been made possible by to the rise of mass communication technologies. It is not as if there no diversity of ideas in the ye olden times, but the ability of people to communicate them was limited, so traditions changed very little from generation to generation. Since then, the world has become more dynamic and chaotic. It has become possible for one person to speak to millions at, without an equal opportunity for the audience to talk back.

Not all things are equally real

Breaking news: a mad scientist has locked a cat in a steel box with a mechanism that may or may not poison it, depending on the roll of a dice. An hour has gone by. Is the cat dead or alive? The easiest way to answer this is to open up the box and check. When that’s not an option, we have a problem. Should the mad scientist be punished? Are all the cats in the neighborhood in danger? What should you do about it?

The point of bringing up the thought experiment known as Schrodinger’s cat is to introduce the idea is that, at least from the subjective perspective of humans, reality is not well-defined. Pretending otherwise can have consequences. For matters where you have no direct knowledge or involvement, it is better to treat the “truth” about it as a black box.

It is helpful to think of it in terms of distance. The closer I am to something, the more “real” it is for me. I am much more qualified to judge a news item about my next door neighbor than one about someone on the other side of the world, because of my personal acquaintance, shared circumstances, and skin-in-the-game (ie. I have a stronger incentive not to jump to conclusions, since the neighbor will be harder to avoid). With increasing physical and mental distance, the object becomes less real and my ability to judge breaks down. Instead of being binary, reality comes in degrees. The less real something is, the less reason I have to bother with it.

A common objection to this idea goes follows: “Even if we don’t know something for certain, we can still make educated guesses. Having some idea of what is going in is better than having none.” This claim assumes that the potential downside of being wrong is significantly smaller than the potential downside of not knowing anything at all. But is that so? It’s a question worth asking, because the answer is not necessarily no, as I pointed out previously on the topic of human nature.

The concept of black-boxing the truth is open to abuse and misinterpretation, particularly in case of moral issues. It is tempting (at least, to the liberal-minded) to think that, since a definitive test is not possible, both sides of a debate are right in their own way. That is not so. The cat is not half-dead or half-alive, it is either dead or alive. The degrees-of-reality concept simply a filtering mechanism, a method to sort by relevance.

The practice of sensationalism suppresses what is relevant

But the real problem with mass media is not the what or how, it is the why. Why should the viewer care about the cat? The news media simply assumes that the viewer cares, because it’s relevant. The viewer ends up “better informed” about topics that are pre-selected. Interestingly, the topics that get the most attention always seem to be the least actionable, either because doing something about it is virtually impossible or there is nothing to be done. It’s not clear what the average viewer is supposed to do (other than worry and obsess) with news about foreign politics and celebrity scandals.

Let’s be honest. For the vast majority of people, useful information is usually contained in the unremarkable, boring details of day-to-day life. None of it is exciting when compared with the juicy tidbits served up by the media. And therein lies the rub.

In other words, high-distance topics seem to get the most attention. Low-distance news items, rarely get any coverage in mass media channels, unless they involve something sensational. This is the main contradiction: what is relevant is out of sync with what is sensational. In fact, the two seem to have an inverse relationship. Ironically, the reason that the media is so relevant is due to its ability to get you to care about irrelevant things.

Is it all a big conspiracy?

Discussions of the power and influence of mass media almost inevitably take on a conspiratorial tone. Explanations found on the internet range from underground lizard people to banal commercial aims. The commercial angle is at least partly accurate, as proven by the zillions of irrelevant, useless ads trying to grab your attention. It also seems plausible that the media (along with other institutions) is, to some extent, doing the bidding of the political and cultural elite.

Funnily enough, the antipathy against mass media has itself become a news item discussed primarily in new-media platforms (YouTube, podcasts, social media). The average viewer lacks direct knowledge or involvement, so this is not different from the average high-distance news item. Fretting over political/corporate intrigues and hidden moral/cultural agendas distracts from the mechanism itself, which is what makes these conspiracies theoretically possible.