Robust versus fragile knowledge, and why mediocrity is not always acceptable

Is it too harsh to always demand excellence and nothing else? In many endeavors of life, it probably is. Unrealistic expectations cause much misery and are often founded on beliefs that exaggerate the importance of said endeavors. Parents and teachers asking straight A’s from students should probably broaden their definition of success.

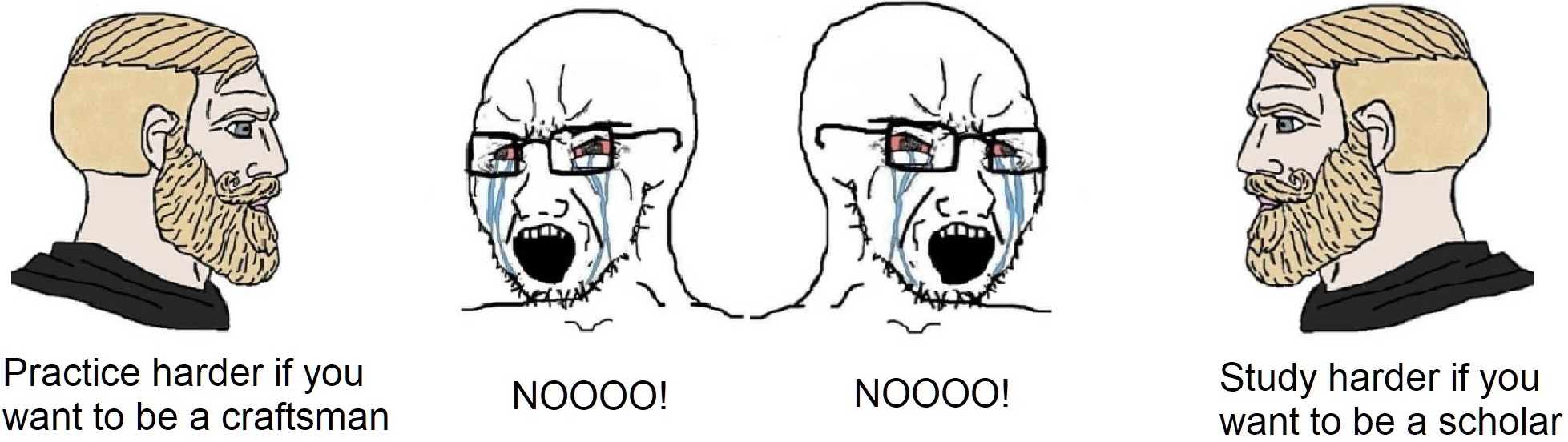

Yet there are cases where such stringent demands are justified, where either of the of the two extremes is preferable to anything in between. Consider how we think about knowledge, how we obsess over factual accuracy and gloss over limitations of our faculties. There are two ways of gaining knowledge: intellectually (“book learning”) and practically (“real life”). Intellectual understanding can be powerful and versatile, but also fragile. A scholar (a truly erudite one, at any rate) must understand that an entire body of knowledge can be invalidated by new observations and should always be on the guard. On the other hand, a craftsman, who has a more workmanlike understanding of the same subject matter, cannot theorize but is also much more robust against the vagaries of theory. An unexpected result in particle physics can make or break the careers of physicists, but bears relatively little significance for the engineers who designed and built the particle accelerators. We have been making tools and tinkering with them since long before Newtonian physics was conceived, and have continued to do so after it became outdated.

Here’s the catch: an intermediate level of knowledge (not erudite enough to be a scholar, not practiced enough to be a craftsman) poses a greater risk than either extremes. Learned scholars and skilled craftsmen know the limits of their knowledge. An electrician will never presume to teach an electrical engineering class on his own. Conversely, a professor of electrical engineering is unlikely to try rummaging through the electrical wiring in his house by himself. But it is easy for someone else to be fooled into thinking that they know something about both types of knowledge, simply because they have heard the professor’s lectures and seen the electrician work a few times. The reality may come as a nasty shock. For any domain where ignorance entails large risks, negative knowledge (estimate of what is yet unknown) is a far safer metric than positive knowledge (accuracy of what is already known).

There are more instances of this principle of extremes being preferable to the center. A good example is the arts. When this idea popped into my head, I kept thinking back to a video essay by Evan Puschak (Nerdwriter1), titled The Epidemic of Passable Movies. The video discusses the recent trends towards mediocrity in Hollywood and why passable movies are worse than ones that are truly good or bad. From a purely entertainment perspective, terrible movies can be fun to watch (The Room, anyone?). Generally, anything with artistic merit appeals to the viewers’ sensibilities. Great filmmakers have mastered both the technical and intuitive aspects, while makers of “bad” movies have some intuition but lack the technical skills to back it up. Passable movies are often the result of trying to cover up deficiency of intuition through competent technique. Filmmakers should be encouraged to follow their ideas, regardless of what critics say, instead of creating soulless mediocrity to pander to an audience.