Genocidal tendencies

I despise the Nazis for all the usual reasons, plus another: they made genocide look so … special. Undoubtedly, modern technology and special circumstances enabled them to carry out massacres on an industrial scale, which are not very common. But is all that pomp necessary for genocidists who are slightly less ambitious? A raving lunatic, a racial ideology, a sophisticated propaganda machine, advanced technology, military might, and legions of supporters are all very helpful. But it is a mistake to think they are prerequisites. Systematic extermination of a particular group of people does not have to well-planned, nor does it have to be immaculate in execution, as long as it is viable and the gains justify the efforts invested.

Is modern civilization somehow more inclined towards genocide than more traditional societies? For those who indulge in the Rousseauan fantasy of the Noble Savage, what we call “civilization” has always represented corruption of human morals, by creating and exacerbating certain immoral activities. But there is little reason to believe that is the case, at least as far as genocide is concerned. It appears that xenophobia and its extreme consequences have accompanied humanity for far longer than can be blamed on modernity. Primitive societies are known to occasionally enagage in mass murder of people outside certain in-groups, as are some of our hominid cousins. While chimpanzees seem to be incapable of building gas chambers and nuclear weapons, we may find some solace, cold comfort as it is, in the fact that Homo sapiens did not invent genocide.

Nevertheless, there is a correlation between genocidal tendencies and the trajectory of human civilization. As different groups of people have come into closer contact, opportunities and incentives for conflict have multiplied. The virtual extermination of New World natives by European invaders provides a glimpse of how less well-documented versions of such activities may have unfolded further back in our history. The United States represents the most recent phase of this occupation. The plight of native Indian tribes in the face of the advancing American frontier is well known. However, conventional history books often fail to mention that this campaign was largely perpetuated by civilians, not organized military forces implementing government policy. Of course, both state and federal governments aided and abetted the settlers, and incentivized them, intentionally or otherwise, to expand the frontier and lay claim to more and more land in the west. But it is a gross oversimplification to think of it as a wholly top-down affair.

Another question is how seemingly “normal” people can, of their own free will, participate in mass murder. Whatever the true explanation is, it is probably not the same as that for opportunistic one-off murders, where the link between motives and actions are much more commonplace. It may be comforting to think that all genocidists have to undergo proper ideological indoctrination before they can slaughter fellow humans like cattle, but history does not support this idea. Well-documented genocides such as the Holocaust involve direct and indirect contributions from ordinary people who seem to lack plausible excuses, such as duress or ignorance. No threats of violence or disinformation were required to convince the average German soldier to shoot Jews in the back of the head and dump their bodies in a mass grave. Rationalizations and peer pressure were enough.

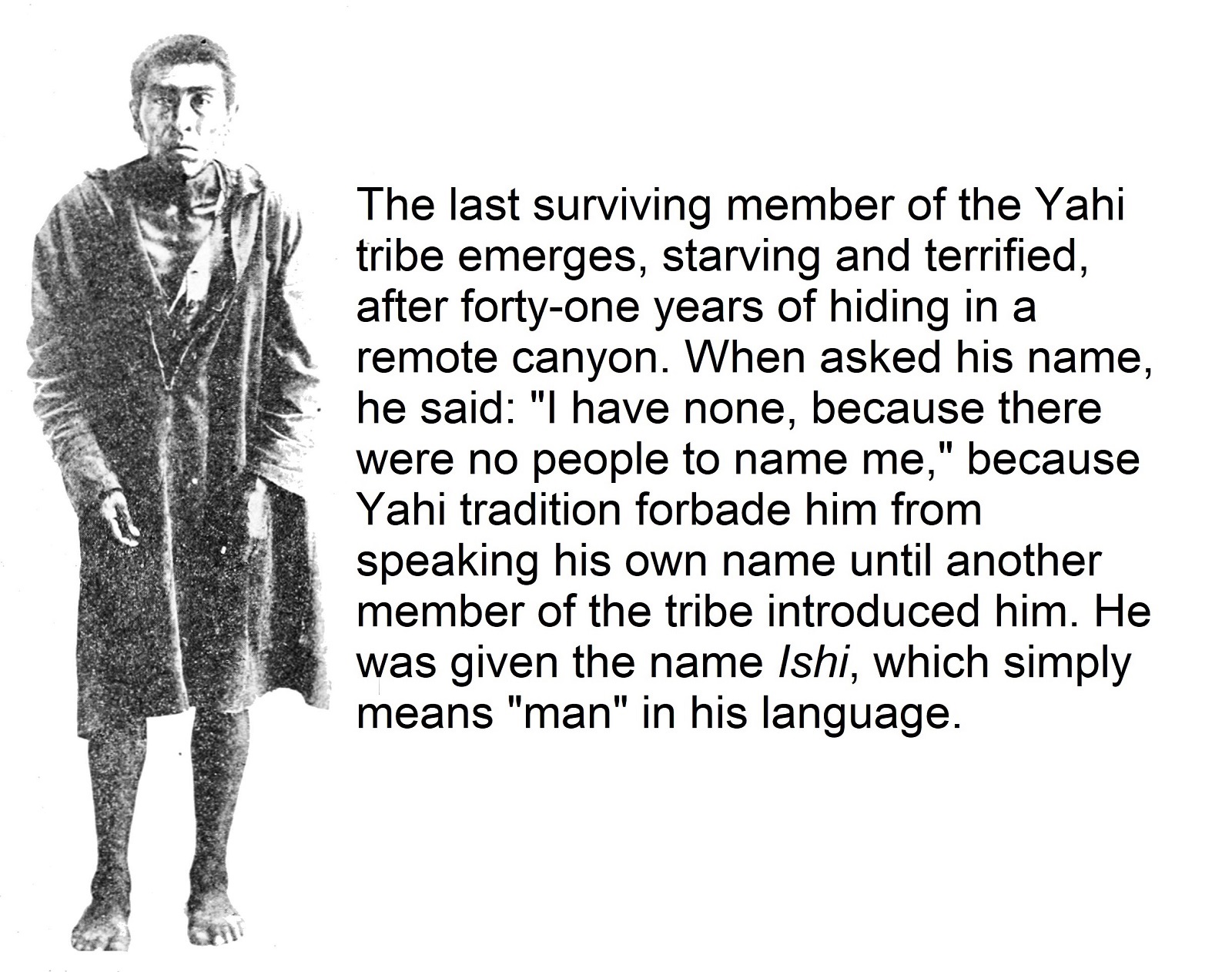

There is one haunting photo that has become permanently associated with the word “genocide” in my memory. It shows Ishi, the last surviving member of the Yahi tribe of northern California in the United States. As the extermination of his tribe by white settlers was nearing completion, Ishi fled into the surrounding forest with fifteen others. Over the next forty-one years, the other survivors died one by one, until Ishi was the only one left. Faced with near certainty of starvation and complete isolation, he chose to walk out of the wilderness instead. The photo shows him as he emerged from hiding, emaciated and terrfied, on August 29, 1911. A death wish, perhaps? However, he stumbled into the light of a world where the massacre of his tribe belonged to the pages of history. Instead of being lynched, he was given a janitor’s job and studied by University of California anthropologists in San Francisco, where he lived out the rest of his days.

Direct violence requires intention, effort, and organization. With a few notable exceptions, cultures are not wiped out by organized campaigns of violence and incarceration alone, mainly because the invaders usually lack the means and incentives for doing so. Displacing people from their native lands, making their way of life difficult, and trying to “civilize” them often produce much better results because these indirect methods require neither conscious intention nor highly organized effort. In fact, to the proper audience, efforts to bring indigenous people into civilization may even be viewed as a kindness! Urbanization and industrialization of native lands, which inevitably destroys the traditional lifestyle, can be justified on the basis of the blessings of modern technology. Could these activities be also classified as genocide? Was dressing Ishi up in a suit and tie a logical continuation of the massacre of his tribe? Without altering the definition of genocide, that would be a misuse of the word. But there’s no denying the roles played by this indirect methods in destroying indigenous cultures.

No matter which side of the nature versus nurture debate you come down on, there’s no escaping the fact that genocidal tendencies have been an unwelcome (and useful, to some people) stowaway on the ship of human progress. But does the real cause even matter at this point? In an age where we can easily imagine humanity being wiped out through sheer incompetence, the question does not seem as important as it once did. But whether or not a satisfactory answer is ever found, I believe that we will always be left wondering about our innocence or lack thereof. Wondering how things could have gone differently, what choices should be made, and whether there is a choice at all.