The Cost of Being Wrong About Human Nature

What are the worst possible consequences if a scientist makes an error?

Accidental black holes? Nuclear annihilation by mistake? An extra year of grad school, perhaps?

Let us dabble in less sci-fi/fantasy and consider something much closer to home: human beings and their behavior.

We can, quite literally, create the world we live in

You can believe that the sun is made out of glowing cheddar cheese or that clouds are really giant heaps of cotton candy without having the slightest effect on what either of those things actually are. The worse that can happen is that you will be labelled an oddball, if you dare to make your pet theories public. Mistaken beliefs about human nature, however, have a much higher cost.

Imagine someone who has been taught since childhood that raw humanity is something to be feared and controlled, because humans in their natural state are selfish, thoughtless degenerates. This view is supported by formal education, admonitions from elders, and popular entertainment. What happens when this person interacts with others who have had the same upbringing? The most likely outcome is that they treat each other with suspicion and act accordingly. These actions, in turn, seem to confirm those old lessons that had been taught and continually reinforced since childhood. The cynical view of humanity becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

This cruel little experiment tells us nothing about original human nature, only that it is possible to render it irrelevant by proper conditioning. The theory predicts the outcome but also creates it.

If Einstein had been wrong about mass-energy equivalence, it wouldn’t be possible to develop the atomic bomb. Believing in his theories wouldn’t magically make nuclear fission work. If one could create gravity by imagining it, Newton’s achievements would have been far less impressive. Natural scientists can be totally wrong without affecting the object of their study, since inanimate objects are indifferent to our beliefs about them. The story is not so simple for the social sciences.

Social sciences are the actual “hard” sciences

Part of the problem stems from the fact that it is harder to get things right in the social sciences, where conducting controlled experiments under perfect laboratory conditions remains something that even the most accomplished academic can only dream of. This lead the biologist Edward O. Wilson to quip that the social sciences are the real “hard” sciences.

The social sciences have always been a minefield. Whether it’s the phenomenon of “physics envy” or the dubious ethics of experimenting on humans, social scientists have always been haunted by the prospect of running headlong into obstacles that simply don’t exist for natural scientists. In the natural sciences, theories are testable (hence falsifiable, to use Karl Popper’s terminology) and it is straightforward to design experiments to prove or disprove them. Human beings, it appears, just don’t yield easily to controlled experiments and elegants theories, not to mention the conflicts of interest that arise when the people developing those experiments and theories have their own vested interests. But scientific accuracy is not all that is at stake here.

Putting people in boxes works, to a certain extent

Not long ago, the psychological school of behaviorism was all the rage among academics. This theory claimed that human behavior was completely determined by the environment, so any behavior could be evoked by properly managing the environment. The psychologist B.F. Skinner was one of the pioneers of behaviorism. As a demonstration of his ideas, he built operant conditioning chambers, also known as “Skinner boxes”, to observe animal behavior in response to environmental stimuli which could be manipulated. Ivan Pavlov, the Russian physiologist famous for his experiment showing that dogs could be made to salivate in response to the sound of bells, was also one of the leading figures in behaviorist theory.

Pure behaviorism is of limited use as a theory of human behavioral development. As psychologists have increasingly realized, we are a product of both nature and nurture. But Skinner boxes do work, and their use doesn’t have to be limited to animals. People can be influenced by their environment, especially the actions of other human beings. It doesn’t matter how “true” behaviorist theory is. The problem is that if any significant grouple of people (especially leaders and policymakers) act as if it’s true, its predictions will appear to be at least partially accurate, simply because people were pushed in a certain direction by belief in the theory itself.

All sciences are not made equal

A long time ago (somewhere in the early to mid-2000s), I read a newspaper article about the winners of that year’s Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences (also known, somewhat controversially, as the Nobel Prize for Economics). The gist of their research was that they had modeled human economic behavior using the physics of gas molecules. I don’t remember the names or any other details about the winners, but I remember being fascinated by the concept.

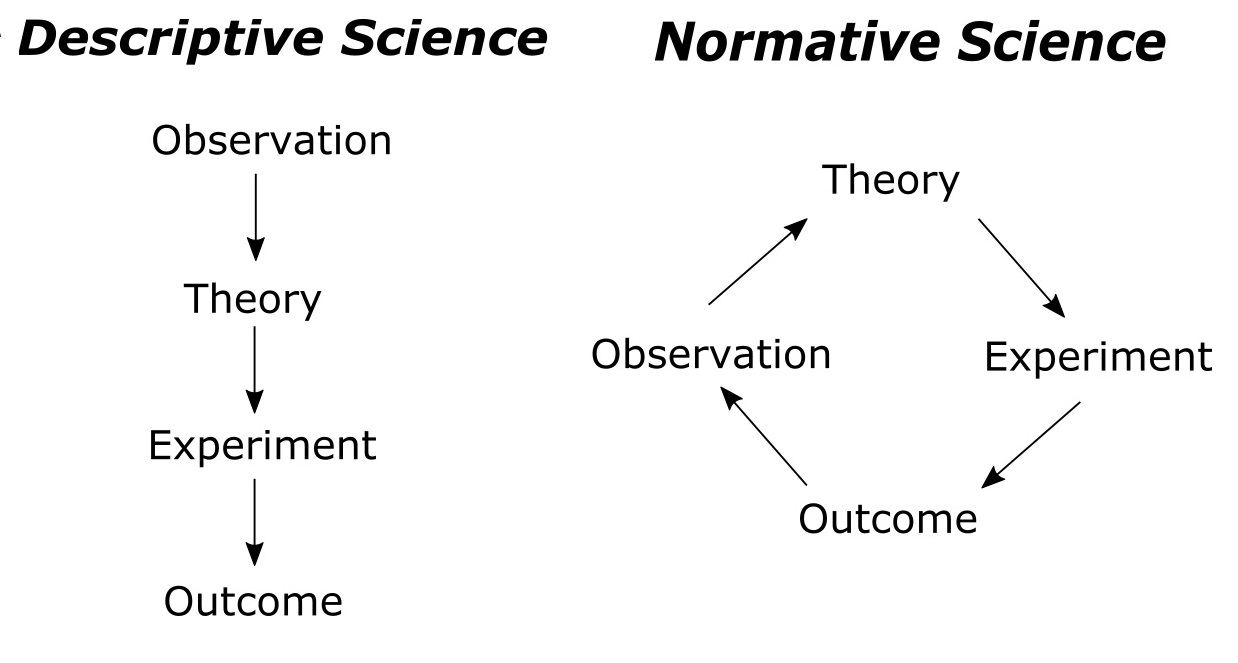

A science can be either descriptive or normative. A descriptive science tries to describes the world as it really is. A normative science specifies “norms” which are blueprints for the world as it should be. Economics, for example, has traditionally been a normative discipline where humans have been modeled as rational (read: selfish), calculating agents, ideally suited to a well-designed market. Not until the recent advent of behavioral economics did this orthodox view come to be challenged by economists themselves. Scientists generally like to think that they are engaged in a descriptive science, but the line between the two categories becomes blurred in the social sciences.

Looking back, I realize that those economists, with their notions about people being just like gas molecules, were not just wrong. Their ideas, along with similar ones from other normative social scientists, are actually harmful.

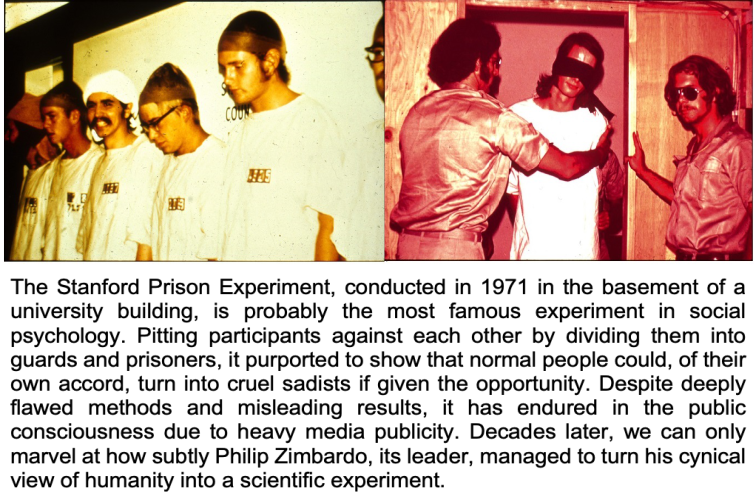

“People are capable of X” and “people will do X” are not the same thing

There is certainly something to the idea that everyone is capable of perpetrating monstrous atrocities. This was the central theme of the book Ordinary Men, which explored the story of a German police battalion, made up of “ordinary” men who had escaped Nazi indoctrination and seemingly not been subjected to any coercion, that conducted masscres of Jews, Gypsies and Poles for no apparent reason other than the fact that they were ordered to do so. The lesson here is that, under the right circumstances, people can be tricked and cajoled into doing evil things. This observation does not mean that, left to their own devices, most people would commit unspeakable crimes. It only means that it is possible to exploit some human characteristics to satisfy the goals of a dedicated minority. When asked about why they went on fighting for Nazi Germany despite imminent defeat in World War II and their lack of commitment to Nazi ideology, many former soldiers said they fought for the sake of their fellow soldiers, not the Third Reich. It hardly seems fair to turn their friendship into the villain just because it happened to serve the interests of the Nazis.

Being wrong about human nature is one the most profound scientific errors (in terms of consequences)

Science cheerleaders think that there can be nothing more damaging to society than believing that climate change is fictional, vaccines cause autism, and the earth is flat. It is debatable to what extent these beliefs have any large-scale impact on world affairs, except maybe convincing legions of science cheerleaders that people are generally dumb and need to be educated and governed intensively before their voices can be heard. Incorrect ideas about human behavior have a much more profound effect on our affairs than incorrect ideas about the natural world. So it’s about time we decide where our priorities lie when we make future policy decisions.

How do we do that?

Avoid large-scale generalization of human beings

Personally, I have adopted the heuristic of avoiding any sweeping generalization of human nature. This includes both armchair theorizing and dubious experiments. Ironically, one of the few generalizations that can be made about human nature is that it’s very tricky to generalize. Left to their own devices and free from warped incentives created by misguided policy, people actually do fine. So why continue with one-size-fits-all thinking and policymaking?

Maybe someday our society will resemble a sci-fi alien supercivilization which can create 3D-printed replicas of a human brain. We will then know our minds as well as we know our personal computers. Social scientists will then be able to achieve their long-cherished dream of scribbling equations on a chalkboard that explain human behavior as well as the behavior of gas molecules. Laws of Human Behavior will be taught in schools alongside Laws of Motion and Gravity.

But until that day comes, let us be skeptical of any large-scale generalization of human nature and its role in policymaking. This skepticism wouldn’t invalidate the social sciences, only reduce their scope and limit their domain of influence. As the natural sciences have shown, generality can be powerful. Let us wield that power cautiously and avoid damaging human nature in the course of studying it.