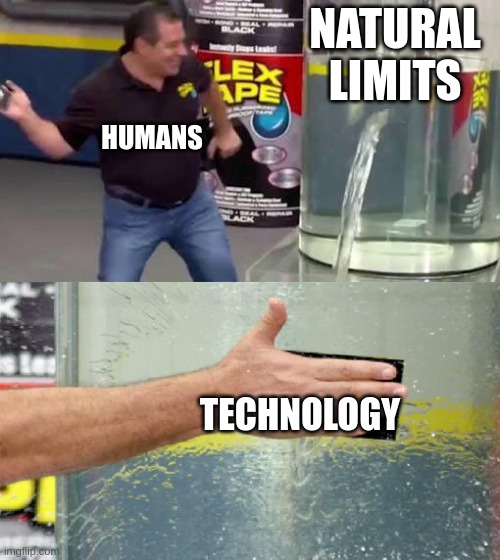

Artificial problems require artificial solutions

We humans are in the habit of thinking of ourselves as problem solvers. The problem exists, so we try to solve it. But that isn’t the full story. Problems and solutions don’t exist in isolation.

Natural “problems” are merely constraints imposed to ensure sustainability

Nature contains self-correcting and self-limiting mechanisms. An ecosystem evolves towards sustainability. Too many predators cause the excess population to starve to death, while an abundance of prey causes a corresponding rise in the predator population. Natural problems have natural solutions. Sustainability cannot be achieved without proper management of finite resources, which requires certain limitations. In the long run, evolution tends to produce sustainable systems because, given enough time, the unsustainable ones are weeded out.

Our prehistoric ancestors faced many dangers: predators, starvation, extreme temperatures, and treacherous terrain, to name a few. Rather than problems to be solved, these factors can be thought of as constraints imposed by nature. A group of people can survive in a given environment as long as overpopulation doesn’t lead to food scarcity and social friction. Certain places are simply not suited for human habitation and must be avoided. Hostile weather and lack of food may also be avoided or mitigated by changing habitats in response to seasonal and environmental changes, instead of hunkering down in one place permanently. These limiting factors only become problems to those who believe that it is our destiny to achieve limitless growth in territory, technology, and population.

Humans are apparently the only organisms who have consistently violated natural limitations

Homo sapiens has certainly proved itself to be a race of inventive and resourceful problem solvers, having freed themselves from complete reliance on genes and relying instead on cultural and linguistic tools for advancement. Yes, other animals may possess something that is recognizable as the crude beginnings of language and culture. But even the best trained chimpanzee or dolphin can hardly compete with a human toddler who has received no special training.

Surely, it’s great that we are no longer chained to our DNA, right? We can acquire new skills, build new systems of knowledge and pass everything on to both current and future members of our species, while other organisms are seemingly incapable of any lasting change without an updated genetic code. This does not seem to be a temporary deviation: we have been doing it for ten thousand years, if the start of agriculture is taken as the starting date. But this freedom is a double-edged sword.

What about human progress? Aren’t we much better off than our predecessors?

Natural constraints are not imposed exclusively on us. However, we appear to be the only species that has broken free of them to any meaningful extent. Food production allowed establishment of settled societies by creating permanent and renewable food sources. Advanced tools and technologies have put much more of this planet (and beyond) within human reach. It seems like nearly all of the material problems faced by our prehistoric ancestors have been solved.

There’s a catch, however. Our unnatural innovations created problems that had not existed before. For example, as more and more nomadic hunter-gatherers turned into sedentary farmers, they became less healthy. People grew less tall, lived shorter, and died sicker. According to a study of skeletal remains by anthropologist Lawrence Angel, it is only within the last century or so that we have regained the level of healthiness enjoyed by our hunter-gather ancestors. Modern medicine certainly allows us to live longer on average (life expectancy has doubled), but mostly it has helped us recover what was lost.

Another such artificial problem, which seems especially relevant in light of the COVID-19, is infectious diseases. Domestication of animals, increasing population density and more frequent contact between previously isolated communities (through trade, migration, and war) created the ideal conditions for such diseases to evolve and spread. Therefore, a second major contribution of modern medicine is to fight a threat that did not even exist in prehistoric times.

Perhaps we should be slightly less enthusiastic when telling the story of human progress. I won’t even delve into the spiritual or psychological issues, since the material evidence provided by cold, hard science should be enough.

What does it matter if a problem is natural or artificial?

As far as our moral obligation to solve these problem, maybe it doesn’t matter. But in case of artificial problems, which were created by human decisions rather than imposed arbitrarily by nature, it may be possible to identify and eliminate the root cause. (There’s technically no reason this cannot be done for natural problems as well, but not without considerable effort and unforeseen consequences. Attempts to “fix” human behavior, for example, can have disastrous results.) This strategy has the advantage of being unlikely to create new problems.

In many cases this will not be a viable strategy. Rolling back human technological progress poses moral quandaries as well as practical hurdles. People, especially the biggest beneficiaries of progress, may be resistant to the idea of giving up the benefits of progress. However, being aware of the root causes may help us make conscious choices about the problems we can live with, rather than being blinded by optimism.

Once in a while, we should be reminded of our potential as problem creators

What’s so groundbreaking about this observation, that solutions can lead to problems? Nothing really. It sounds quite ordinary, like something that doesn’t even need to be said out loud. Yet, it’s worth repeating, again and again, because it’s one thing to make a trite, generic observation and quite another to apply it in the real world. In the real world, memories are short and true costs are hidden, so the link is rarely obvious. The narrative of modernity casts humans in the role of problem solvers, but they are problem creators too. This reminder would, I hope, prevent the endless chain of solutions creating more problems.